In the last blog post we considered what the basic structure of the information packages should look like and how we will deal with versioning. In the following I would like to describe further cornerstones of a minimalistic archival information system. These will then form the basis for a first implementation, which would go beyond the scope of this blog. As soon as there is news worth reporting, I will announce it here.

Data management

Other archival information systems sometimes make it too easy for themselves and use a database to manage information about the AIPs in the archive. In principle there is nothing wrong with this, but it often seems that it is forgotten that a basic principle of information packages is the intellectual unit (IE) of data and metadata. What does this mean? The idea is that an IE should be able to stand on its own at all times. Following this principle has two consequences. First, hierarchically nested IEs cannot exist unless self-contained IEs are encapsulated like a box of boxes. In other words: IEs that only contain references to other IEs are not possible because they would not be viable on their own.

The second consequence is that all metadata must always be in a consistent state, regardless of the state of the archive information system. In other words, there must be no contradictions between the information stored in the AIP and the information in the system's database.

Why is this important? The Archival Information Packages are ultimately the time capsules that will outlast the Archive. If everything breaks, but a copy of an AIP is still found on tape, it contained all the information needed to interpret the data to be preserved.

So for the management of the AIPs we define the following:

- the AIP is the basis for everything. If there are inconsistencies in the archival information system, we first ask the AIPs.

- In order to speed up the processing, we can use a database. But then there must be a way to generate the database from the AIPs.

- If the AIP is the basis for everything, then we need a mechanism that ensures that if there are errors in the creation of an AIP or in the creation of a new AIP version, these can be rolled back.

- The archive can and should only assume responsibility for the data entrusted to it if an AIP or a new AIP version could be successfully generated.

Things that make life easier

What has proven to be very helpful is the following:

- We should only allow 1:1 mappings. This means that a SIP contains exactly one digital object

- We do without nested IEs.

- We ignore for now that copy operations are expensive. It follows that AIP updates always consist of SIPs with complete data and metadata.

Architectural decisions

A minimalist archival information system (MAIS) should have the following properties:

- Implemented as open source for study, improvement and reuse

- Command line oriented so there is a clear interface.

- Concentration on the essentials, therefore no routing, but suitable for parallel use.

- Fast and small enough not to waste resources.

- Avoiding XML to keep code simple and metadata human-readable

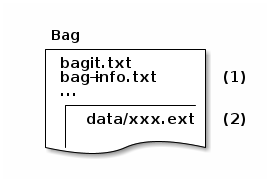

- BagIt as base for SIPs, AIPs and DIPs

- Preservation Planning and Action as an external operation on a set of AIPs

- Implementation in a programming language that can be used for all common operating systems without contortions.

And now?

I plan to tackle the programming in the coming weeks and months. I will probably not go into detail about the individual steps of programming here. As soon as there is something presentable, I'll let you know. Otherwise let me know what your experiences are, which details are important to you with an AIS, especially if it should be particularly lightweight.